The first test I ever failed was about identifying different parts of speech. I believe I was in 3rd or 4th grade, and I was devastated. The rest of my class didn’t achieve particularly high scores either, but I had never failed anything! What was it that I was missing about finding nouns in a sentence? Why didn’t adverbs make more sense? Overall, the attitude that I developed towards grammar in elementary school was one of confusion, frustration, and intense dislike. This attitude would follow me through middle school and high school until I enrolled in a Linguistics class as a freshman in college where I learned about the practice of diagramming sentences.

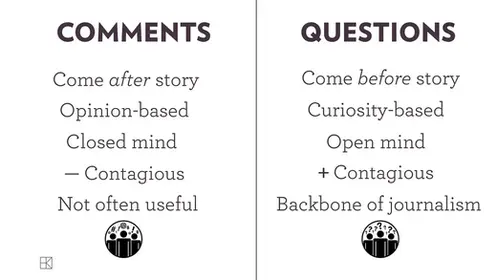

I don’t believe that my early experiences with grammar are unique. For years, educators have taught grammatical concepts in isolation. Students would learn about one part of speech at a time, complete some worksheets about it, and take a test only to promptly forget what that part of speech was about when they moved on to the next one. This type of instruction also fails to help students apply useful rules of grammar and parts of speech to their own writing. These issues are precisely why my teaching instructors in college advocated for a completely new approach to teaching grammar.

The Modern Approach to Grammar

While working toward my undergraduate degree in English education, my professors encouraged an approach to grammar that allowed students to see the real-life application of grammatical concepts. We were instructed to show students mentor texts where famous authors used interesting grammatical techniques. We were told to model those techniques for the students without focusing on the terminology of what we were doing. We were directed to have students try those ambiguous, nameless techniques, so they could see that their own writing could look professional as well. This approach to grammar sounded excellent! In practice, it was a nightmare.

The Problems

I began teaching English to 7th and 8th grade public school students in the fall of 2018 when I was fresh out of college. I was eager to apply the learning theories that I had studied throughout the four years of my undergraduate degree. After meeting my students and reading some of their writing, I knew that they could benefit from grammar instruction. I set up a lesson with mentor texts, modeling, and student practice. I went into my grammar lesson confident and excited to share writing techniques with my students. The mentor texts were wonderful. Students enjoyed seeing the excellent things that authors can do with their writing. The entire lesson might have gone perfectly, except that my students had questions.

“Ms. Johnsen, what do you call this?”

Well, it is called a participial phrase. It is a piece of a sentence that contains a participle word. Altogether, it describes something else in our sentence.

“Ms. Johnsen, what is a participle?”

A participle is a word that looks like a verb but acts like an adjective.

“Ms. Johnsen, what is an adjective?”

An adjective is a word that describes a noun.

“Ms. Johnsen, what is a noun?”

I learned quickly that my students didn’t have a foundation to build on when it came to grammar. How could I explain the benefits of using participial phrases when students didn’t understand the terminology around how the phrase was working? How could I cover the 8th grade Common Core literacy standard L.8.1.a that asks me to explain the functions of verbals when my students didn’t know what a noun, adjective, or adverb were? How could I explain where to put a comma in a compound sentence when my students didn’t know how to identify a subject or a verb?

I don’t believe that my professors were wrong. Mentor texts are wonderful, and it is exceptionally beneficial for students to learn that they can use the same techniques as professional writers. Modeling writing strategies before students try them is encouraging. Teaching grammar instruction in conjunction with writing is essential. What I also believe to be true is that students need a strong foundation in the essential components of a sentence before they can comprehend and accurately apply the more advanced and creative methods that English teachers dream of seeing while grading essays and short stories.

There will always be students who read profusely and pick up techniques from the authors they love most. I have worked with such young writers, and they impress me to no end. These types of writers also need a foundation of grammatical knowledge in order to understand the finer points of punctuation and the “why” behind how they are writing. I have come across very creative writers who use wonderful strategies but don’t know how to improve their writing even further. Even advanced writers could use a base knowledge in clauses to understand how to vary the types of sentences they use or how to use a semicolon correctly.

Unfortunately, not all students are passionate about writing. In fact, I believe the majority of students that I have worked with truly do not enjoy writing. It is an intimidating, frustrating, and time-consuming process for many students in all grades. Those students who hate writing and struggle to put any sentence together are the reason I enjoy teaching sentence diagramming.

A Solution: Sentence Diagramming

Sentence diagramming is the practice of drawing out sentences to create a visual representation of the job each word is performing and the sentence’s overall structure. I call sentence diagramming “mapping” out sentences because we use lines to see the connections and relationships between the words in a sentence. Not only does a learner see how the word is working on its own, they also see how the words are working together to make meaning. This practice reveals patterns in the English language that students may not come across by learning about the parts of speech in isolation.

What’s more, diagramming reveals punctuation rules that might otherwise elude writers for years. Most students I meet, regardless of their age, tell me that they have heard of a semicolon, but they have no idea how to use it. This response is true for most adults that I discuss grammar with as well! By lesson 9 of my diagramming course, students can identify the instances in which they could use a semicolon, and they can explain why.

Sentence diagramming may seem archaic, but there are ways to make building a grammatical foundation with this method fun and applicable. First, I find it important to treat sentence diagramming like the puzzle that it is. Each sentence should be approached with curiosity and excitement that encourages students to unravel the mysteries it holds. The excitement and interest that a teacher has for a topic should be evident to the students, as these feelings can help them approach the topic positively as well. It is also important that students have the opportunity to practice what they learn about sentence structure and the parts of speech through their own writing. Each diagramming lesson that I teach ends with asking students to write a sentence or two that demonstrates what they learned in the lesson. In this way, students are able to apply what they learn to their own writing to see the benefits of knowing about grammar.

I have seen absolutely amazing results with teaching diagramming in a classroom and online. I feel that diagramming instruction is most beneficial in short bursts. While in a classroom, I spent 5-10 minutes on sentence diagramming instruction at the beginning of each class. I called this practice Sentence Diagramming Bell Ringers, which provided the students with short, repetitive practice focused on the parts of speech and sentence structure. My special education co-teacher and I were thrilled to see ALL students confidently identifying nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, and comma placement for compound sentences all within a few short months of practice for 5-10 minutes each day.

Online, I teach Beginner Sentence Diagramming and Advanced Sentence Diagramming for 30 minutes twice per week. As with the bell ringers, these courses include a slow progression of adding new parts of speech or diagramming techniques one at a time. Additionally, both courses and bell ringers include quite a lot of repetitive practice. Once students learn a new technique, I ask them to use their knowledge again and again throughout the following lessons. This process of recall and application is an extremely important piece of helping the parts of speech and sentence structure rules stick.

Overall, I am continually impressed by the results of sentence diagramming instruction for students. I wish that my teachers could have introduced this approach to me back in elementary school. Perhaps I wouldn’t have developed the intense distaste for grammar at such a young age that continued throughout middle and high school. It is comforting to know that as a teacher, I have the privilege of introducing young learners to grammar in a comprehensive, applicable, and fun way.

My name is Shannon Johnsen, and I am a licensed 5-12 English educator in the state of Minnesota. After completing my bachelor's degree and receiving my teaching license, I attended the University of Missouri to pursue a Master's of Education in Educational Psychology. I spent four years teaching 7th and 8th grade English in a public school. In 2022, I took the leap to online teaching, and I absolutely love it. I am passionate about literature, grammar, and social emotional learning. To learn more, please visit my educator profile.

.png)

We'd love to hear your thoughts! Leave a comment below.